- U.N.: Sectarian conflict in the Central African Republic kills more than 600 people

- The new atrocities raise questions about what has changed since Rwanda

- "You've got to take action to stop it," expert says

- The United Nations and United States are reluctant to intervene militarily

Washington (CNN) -- Another African milestone, another African tragedy.

In 1994, a stunning array of world leaders gathered in South Africa to celebrate Nelson Mandela's inauguration while genocidal massacres spread in Rwanda.

Now, the world focuses on South Africa again -- this time for Mandela's funeral -- as warnings of potential genocide emanate from Central African Republic.

The ironic juxtaposition of the greatest example of African reconciliation with horrific carnage elsewhere on the continent raises the question of what has changed in the 19 years since Rwanda to prevent the kind of targeted exterminations the world repeatedly vows to stop from happening again.

Crisis in the Central African Republic

Crisis in the Central African Republic If the situation in Central African Republic is the guide, the answer is some change has occurred, but probably not enough.

Chaos in Central African Republic

Chaos in Central African Republic Conflict in Central African Republic

On Friday, the U.N. high commissioner for refugees reported more than 600 deaths and 159,000 people displaced in the impoverished landlocked nation because of sectarian violence involving Muslim and Christian militias.

According to the report, the situation in Bangui, the capital, continued to deteriorate despite the presence of French and African Union forces sent to restore order and disarm the rival militia groups. Tens of thousands of refugees have fled to neighboring countries or gathered at the Bangui airport, which is being secured by foreign troops, it said.

The aid group Medecins Sans Frontieres slammed the United Nations this week for what it called an unacceptable humanitarian response, echoing similar frustration and despair heard from witnesses to looming crises in Rwanda and elsewhere in recent decades.

At the same time, the ongoing arrival of up to 1,200 French troops and 6,000 African Union forces drawn from several countries reflects a shift since Rwanda that put more responsibility for regional peacekeeping on Africans while demonstrating a willingness to act -- even if in a limited way -- in the face of atrocities.

To Gregory Stanton, a genocide expert at George Mason University in Virginia, the international response so far is lacking in a conflict that he believes "is genocidal already."

Stanton, who heads the nonprofit group Genocide Watch, said genocide occurs any time there are massacres targeting victims based on race, ethnicity, religion or nationality.

"If you have mass killings, whether it's based on religion or politics or whatever, we think that's bad enough," he said. "You've got to take action to stop it."

Rwanda symbolizes global failure

The Rwanda genocide, in which hundreds of thousands of people died over three months of ethnic attacks, remains the symbol for ineffective international response to African carnage.

U.N. peacekeepers scaled back as the organized Hutu slaughter of Tutsis escalated, and the world body and Western powers, including the United States, were blamed for failing to intervene more forcefully.

"The genocide in Rwanda has caused an enormous amount of soul-searching, particularly in the West," noted John Campbell, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former U.S. ambassador to Nigeria.

Now, he said, there remains "a sense that this absolutely should not have happened," as well as frustration in Washington and other capitals "over what in fact could have been done or should have been done."

Stanton described deep rifts in the Clinton administration at the time between officials favoring or opposing stronger intervention.

In particular, he cited a telephone screaming match between then U.N. Ambassador Madeleine Albright and National Security Council official Richard Clarke over orders for Albright to vote for withdrawal of U.N. peacekeepers in the face of the suddenly escalating violence.

"I just wish that it had not been something that the international community was not capable of dealing with," Albright told PBS in a 2004 interview.

Black Hawk Down effect

Campbell traced the U.S. reluctance to get more involved in Rwanda to the infamous intervention in Somalia less than two years earlier.

With famine and political dysfunction causing widespread starvation, the United States sent Marines to the East African country in December 1992 as part of an international force intended to restore order and get aid properly distributed.

However, the lack of functioning governance led to increasing sectarian violence, an expanded U.S. mission and the Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993, in which two U.S. Black Hawk helicopters were shot down and 18 American soldiers died while more than 70 were injured.

The event, which inspired the Hollywood film "Black Hawk Down," turned public opinion against continued U.S. involvement in Somalia.

"It showed the extremely limited domestic tolerance for intervention in Africa, particularly if it involves American lives," Campbell said.

He praised France for sending troops to Central African Republic now, noting a similar French commitment to a former colony when it intervened militarily in Mali in January with 4,000 troops to battle Islamist militants.

"The French seem to have much greater tolerance for casualties but also much greater support for French intervention" in countries it once colonized, Campbell said.

A caretaker role for its former colonies provides France with a sense of national prestige for its sphere of influence, as well as support as part of a Francophone bloc in international bodies such as the United Nations and World Trade Organization, he said.

Expert: Proper intervention saves lives

Stanton also lauded France for sending forces, but said the world needs to do more. He called for a much stronger military intervention, calling it the only way to effectively prevent what he labeled "serial killers going around and killing civilians."

"If you can send in a force that's so awesome that it will scare these militias into actually stopping and dropping their arms, you'll actually save lives," he said, asserting that the cost-effectiveness of intervention was far superior to dealing with the aftermath.

"For maybe $200 million we could have stopped the Rwandan genocide" instead of spending billions on relief aid, Stanton said, adding: "It's always less expensive to stop a genocide than to clean up afterwards."

In the 2004 PBS interview, Albright agreed with Stanton but said the realities of U.N. and U.S. politics at the time made such an intervention impossible.

"In retrospect, the thing that might have made sense is for a massive humanitarian intervention led by a major country; if not the U.S., then somebody else," she said. "But that was not even vaguely in the cards at the time."

Samantha Power, the current U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, won a Pulitzer Prize for her 2002 book "A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide" that posed the question of why the United States would "stand so idly by" when mass atrocities occur.

In a 2003 speech, Power described how the visceral reaction to genocide was to look away instead of getting involved.

"It's almost as though the worse the crime, the more likely we are to say, 'ugh, who can begin to go there, who can begin to think about making a difference when you have 8,000 people being murdered a day and bodies piling up around the U.S. Embassy and other outposts' " she said.

Religious violence in CAR plagues 'most abandoned place on earth'

U.N. Convention on Genocide

For years, Power noted, Congress avoided ratifying the 1948 U.N. Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, initially because senators from Southern states feared "Jim Crow" discriminatory laws could be cited as violations.

Even when the United States joined the convention in 1988, the pact had "very little bearing on the U.S. response to subsequent genocides," Power said.

In particular, she said, U.S. leaders refused to use the "G-word" to describe conflicts because "the feeling was in the United States government that it would oblige the United States to do things that it was otherwise ill-inclined to do."

After Rwanda, the United Nations and U.S. policy sought a more collaborative relationship with African nations on regional peacekeeping, partly to enable faster reaction and partly to avoid getting the full blame for failures as occurred with Rwanda.

"There has been a confluence between the Western and African approaches, which is African solutions to African problems, but with significant Western support but not boots on the ground," Campbell said, attributing the change to uncertain public support in Western countries for African intervention. "No democratic government can pursue very long a policy of outside intervention without popular support."

For the Obama administration, the issue of African intervention has been influenced by efforts to contain expanding al Qaeda influence on the continent.

NGO slams U.N. work in Central African Republic

President Obama's policy

A new policy announced in 2012 aimed at preventing mass atrocities included a series of steps at home and abroad that reflected better planning mechanisms and more collaborative efforts.

In a fact sheet released in May on the progress of the new policy, the administration cited the creation of an Atrocities Prevention Board comprising officials from across the government and military including the State Department, Pentagon, Treasury, Justice Department, Homeland Security, CIA, the vice president's office and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

According to the fact sheet, the board identifies emerging atrocity threats, assesses the risk of mass atrocities and takes steps to "ensure that atrocity threats receive adequate and timely attention."

However, there has been little public information on the board beyond the fact sheet, which listed steps taken so far including enhanced early warning measures, expanded use of sanctions and offering rewards to crack down on perpetrators, and "sharing the global burden by strengthening multilateral institutions and bolstering international peacekeeping capabilities."

That has meant involvement of the U.S. military in some cases.

"In central Africa, U.S. forces and civilian experts continue to advise and assist regional partners to counter the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) , building on our comprehensive strategy, which also includes protecting civilians, encouraging defections, and providing humanitarian assistance," the fact sheet said in reference to the notorious armed group originally from Uganda now on the run in the region.

U.S. airlift of French, African Union troops

The administration announced this week that it was committing $60 million to support the French and African Union troops in Central African Republic, including planes to transport them in and out of the country.

"We are willing to provide the airlift. That is a huge change," Stanton said. "We weren't willing to do that in Rwanda."

The tactics reflect Obama's preference for taking a supporting role in international operations, such as providing support for NATO intervention in Libya in 2011 led by European allies Britain, France and Italy.

Violence has plagued Central African Republic since a coalition of Muslim rebels deposed President Francois Bozize in March, the latest in a series of coups since it gained independence from France in 1960.

French troops deployed alongside the African forces in a peacekeeping mission aimed at restoring security, protecting civilians and ensuring access to humanitarian aid.

It was unclear if it might escalate into the kind of slaughter that occurred in Rwanda, something that Albright warned in 2004 was hard to detect.

"The truth is that, unfortunately, every genocide ends up being slightly different, and they look more evident in retrospect than they do at the time," she told PBS. "One would hope that the lessons of Rwanda would be that you have to respond instantly. But you can't be sure."

Report: Political instability on the rise

CNN's Pierre Meilhan, Laura Smith-Spark and Nana Karikari-apau contributed to this report.

The Archibishop of Bangui, Dieu Donne Nzapa Lainga preaches on Saturday, December 14 to people gathering at a refugee camp close to the Bangui airport. France has begun a military operation in the nation and has been dealing with violence since a March coup. U.S. military aircraft will begin flying African and European peacekeepers into the country, which is in the midst of a bloody civil war between various Christian and Muslim militias and other rebel factions.

The Archibishop of Bangui, Dieu Donne Nzapa Lainga preaches on Saturday, December 14 to people gathering at a refugee camp close to the Bangui airport. France has begun a military operation in the nation and has been dealing with violence since a March coup. U.S. military aircraft will begin flying African and European peacekeepers into the country, which is in the midst of a bloody civil war between various Christian and Muslim militias and other rebel factions.  Anti-Balaka fighters, members of a militia opposed to the Seleka rebel group, pose with weapons and amulets in a village in the Boy-Rabe neighborhood in Bangui on December 14.

Anti-Balaka fighters, members of a militia opposed to the Seleka rebel group, pose with weapons and amulets in a village in the Boy-Rabe neighborhood in Bangui on December 14.  A Seleka presidential guardsman smokes at the downtown market in Bangui, Central African Republic, on December 14.

A Seleka presidential guardsman smokes at the downtown market in Bangui, Central African Republic, on December 14.  Christians gather in a makeshift camp for internally displaced people set in the airport in Bangui on Friday Dececember 13.

Christians gather in a makeshift camp for internally displaced people set in the airport in Bangui on Friday Dececember 13.  Muslim men rough up a Christian man while checking him for weapons on December 13 in Bangui.

Muslim men rough up a Christian man while checking him for weapons on December 13 in Bangui.  Troops from the Multinational Force of Central Africa, regional peacekeepers, shoot as they attempt to evacuate Muslim clerics from the St. Jacques Church in Bangui on Thursday, December 12. An angry crowd had gathered outside the church following rumors that a Seleka general was inside.

Troops from the Multinational Force of Central Africa, regional peacekeepers, shoot as they attempt to evacuate Muslim clerics from the St. Jacques Church in Bangui on Thursday, December 12. An angry crowd had gathered outside the church following rumors that a Seleka general was inside.  The bodies of 16 Muslim men are loaded onto a truck at the Nour Islam Mosque before being transported for burial in Bangui on Wednesday, December 11.

The bodies of 16 Muslim men are loaded onto a truck at the Nour Islam Mosque before being transported for burial in Bangui on Wednesday, December 11.  A young woman holds her baby at an elementary school in the Muslim district of Bangui on December 11.

A young woman holds her baby at an elementary school in the Muslim district of Bangui on December 11.  People pray as they bury 16 coffins in a Muslim cemetery in Bangui on December 11.

People pray as they bury 16 coffins in a Muslim cemetery in Bangui on December 11.  French troops detain a suspected Seleka officer -- preventing a Christian mob from lynching him -- in Bangui on Monday, December 9.

French troops detain a suspected Seleka officer -- preventing a Christian mob from lynching him -- in Bangui on Monday, December 9.  French soldiers arrest an alleged ex-Seleka rebel in a neighborhood near the airport in the capital of Bangui on December 9.

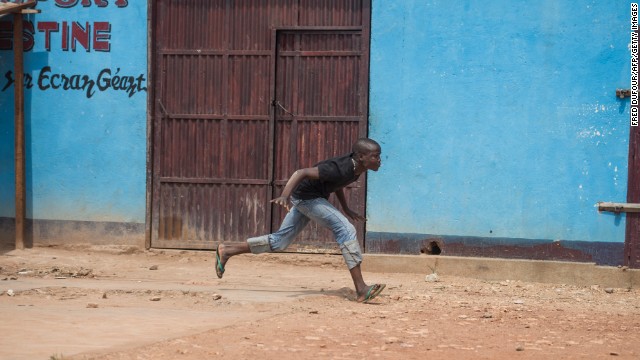

French soldiers arrest an alleged ex-Seleka rebel in a neighborhood near the airport in the capital of Bangui on December 9.  A man runs from a gunfire during a disarmament operation by French soldiers in Bangui on December 9. Violence has raged since a coalition of rebels deposed President Francois Bozize in March, the latest in a series of coups since the nation gained independence. Bozize fled after his ouster.

A man runs from a gunfire during a disarmament operation by French soldiers in Bangui on December 9. Violence has raged since a coalition of rebels deposed President Francois Bozize in March, the latest in a series of coups since the nation gained independence. Bozize fled after his ouster.  People gather around an alleged ex-Seleka rebel as he is arrested by French soldiers in Bangui on December 9. French soldiers began disarming fighters after a swell of violence. Christian vigilante groups have formed to battle Seleka, the predominantly Muslim coalition behind the president's removal.

People gather around an alleged ex-Seleka rebel as he is arrested by French soldiers in Bangui on December 9. French soldiers began disarming fighters after a swell of violence. Christian vigilante groups have formed to battle Seleka, the predominantly Muslim coalition behind the president's removal.  People walk by a French soldier standing guard during a disarmament operation in Bangui on December 9.

People walk by a French soldier standing guard during a disarmament operation in Bangui on December 9.  A French soldier stands guard after the arrest of ex-Seleka rebels in a neighborhood near Bangui's airport on December 9.

A French soldier stands guard after the arrest of ex-Seleka rebels in a neighborhood near Bangui's airport on December 9.  French soldiers stand guard near a man they have arrested in Bangui on December 9.

French soldiers stand guard near a man they have arrested in Bangui on December 9.  French troops patrol past two Seleka vehicles suspected of being set on fire by Christian mobs in Bangui.

French troops patrol past two Seleka vehicles suspected of being set on fire by Christian mobs in Bangui.

A French soldier speaks to a suspected Christian militia member who was wounded by a machete in the Kokoro neighborhood of Bangui on December 9. Vigilante crowds said they spotted him with grenades and turned him in to French forces. Both Christian and Muslim mobs went on lynching sprees as French forces deployed in the capital.

A French soldier speaks to a suspected Christian militia member who was wounded by a machete in the Kokoro neighborhood of Bangui on December 9. Vigilante crowds said they spotted him with grenades and turned him in to French forces. Both Christian and Muslim mobs went on lynching sprees as French forces deployed in the capital.  Mobs of Christians grab a child holding a knife in Bangui on December 9.

Mobs of Christians grab a child holding a knife in Bangui on December 9.  Children attend a mass given by the Archbishop of Bangui at Saint-Paul's parish on Sunday, December 8.

Children attend a mass given by the Archbishop of Bangui at Saint-Paul's parish on Sunday, December 8.  Children ask for biscuits at a base camp held by the French military in Bossembele on December 8.

Children ask for biscuits at a base camp held by the French military in Bossembele on December 8.  Red Cross employees stand amid dozens of bodies at the morgue in Bangui on December 8. The number of corpses delivered to a hospital morgue in the city rose Friday afternoon to 92, according to Doctors without Borders.

Red Cross employees stand amid dozens of bodies at the morgue in Bangui on December 8. The number of corpses delivered to a hospital morgue in the city rose Friday afternoon to 92, according to Doctors without Borders.  Michel Djotodia, Central African Republic's president, gives a press conference in his office in Bangui on December 8. French forces fanned out across the town Sunday, as Seleka forces kept their patrols despite an order to return to their barracks.

Michel Djotodia, Central African Republic's president, gives a press conference in his office in Bangui on December 8. French forces fanned out across the town Sunday, as Seleka forces kept their patrols despite an order to return to their barracks.  A displaced child walks in Bangui on December 8. More than 400,000 people -- nearly 10% of the population -- have been internally displaced, according to the United Nations.

A displaced child walks in Bangui on December 8. More than 400,000 people -- nearly 10% of the population -- have been internally displaced, according to the United Nations.  Relatives of Thierry Tresor Zumbeti, who died from bullet wounds to the neck and stomach, grieve outside his home in Bangui on Saturday, December 7.

Relatives of Thierry Tresor Zumbeti, who died from bullet wounds to the neck and stomach, grieve outside his home in Bangui on Saturday, December 7.  A former member of the militia that led the coup against the Central African Republic's president sits next to a machine gun as he and others stand guard at a shut-down market in Bangui on December 7.

A former member of the militia that led the coup against the Central African Republic's president sits next to a machine gun as he and others stand guard at a shut-down market in Bangui on December 7.  Children play inside Bangui's Saint-Bernard Church, where their families took refuge following the wave of deadly violence, on December 7.

Children play inside Bangui's Saint-Bernard Church, where their families took refuge following the wave of deadly violence, on December 7.  French soldiers patrol on a road in Baoro on December 7 as part of the military operation aiming at restoring security in the Central African Republic.

French soldiers patrol on a road in Baoro on December 7 as part of the military operation aiming at restoring security in the Central African Republic.  A French soldier watches the road in Baoro on Saturday, December 7.

A French soldier watches the road in Baoro on Saturday, December 7.  People grieve for a man killed in Bangui on December 7.

People grieve for a man killed in Bangui on December 7.  Women push a coffin in the streets of Bangui on December 7.

Women push a coffin in the streets of Bangui on December 7.  A French helicopter lands at a base camp in Cameroon on Friday, December 6.

A French helicopter lands at a base camp in Cameroon on Friday, December 6.  The U.N. Security Council votes Thursday, December 5, to authorize increased military action in the Central African Republic. The resolution, put forward by France, authorizes an African Union-led peacekeeping force to intervene with the support of French troops.

The U.N. Security Council votes Thursday, December 5, to authorize increased military action in the Central African Republic. The resolution, put forward by France, authorizes an African Union-led peacekeeping force to intervene with the support of French troops.  People stand near bodies found lying in a mosque and in its surrounding streets in the Central African Republic capital of Bangui on December 5.

People stand near bodies found lying in a mosque and in its surrounding streets in the Central African Republic capital of Bangui on December 5.  French military forces drive in Cameroon on December 5. The mission of the peacekeeping force is to protect civilians in the Central African Republic, restore humanitarian access and stabilize the country.

French military forces drive in Cameroon on December 5. The mission of the peacekeeping force is to protect civilians in the Central African Republic, restore humanitarian access and stabilize the country.  Civilians wait for treatment at Bangui's hospital after a daylong gun battle between Seleka soldiers and Christian militias on December 5. Christian vigilante groups have formed to battle Seleka, the predominantly Muslim coalition behind the March removal of President Francois Bozize.

Civilians wait for treatment at Bangui's hospital after a daylong gun battle between Seleka soldiers and Christian militias on December 5. Christian vigilante groups have formed to battle Seleka, the predominantly Muslim coalition behind the March removal of President Francois Bozize.  A nurse tends to the wounded at Bangui's hospital on December 5.

A nurse tends to the wounded at Bangui's hospital on December 5.  Seleka soldiers race through Bangui as gunfire and mortar rounds erupt in the capital December 5.

Seleka soldiers race through Bangui as gunfire and mortar rounds erupt in the capital December 5.  Wounded civilians lie on the floor of Bangui's hospital on December 5.

Wounded civilians lie on the floor of Bangui's hospital on December 5.  Seleka soldiers patrol Bangui on December 5.

Seleka soldiers patrol Bangui on December 5.  A severely wounded man lies unattended in a Bangui mosque December 5.

A severely wounded man lies unattended in a Bangui mosque December 5.  Shrouded bodies are seen in a Bangui mosque December 5.

Shrouded bodies are seen in a Bangui mosque December 5.  Civilians seek shelter in a Catholic church in Bangui on December 5.

Civilians seek shelter in a Catholic church in Bangui on December 5.  A Seleka soldier is briefed while manning a checkpoint in Boali, Central African Republic, on Wednesday, December 4.

A Seleka soldier is briefed while manning a checkpoint in Boali, Central African Republic, on Wednesday, December 4.  Christians from the village of Bouebou load up on a taxi as they flee violence on December 4.

Christians from the village of Bouebou load up on a taxi as they flee violence on December 4.  Christian children from Bouebou are packed in the trunk of a taxi as they flee violence December 4.

Christian children from Bouebou are packed in the trunk of a taxi as they flee violence December 4.

No comments:

Post a Comment