- Bob Greene says Olympics thankfully didn't echo 1960s competition between superpowers

- He says when Soviets, U.S. competed in space race, the goal galvanized Americans

- He says they saw Kennedy's moon goal as repudiation of Khrushchev's "bury you" remark

- Greene: U.S. got there first; today, there's no race, just friendly competition, like in Sochi

Editor's note: CNN Contributor Bob Greene is a bestselling author whose 25 books include "Late Edition: A Love Story"; "Duty: A Father, His Son, and the Man Who Won the War"; and "Once Upon a Town: The Miracle of the North Platte Canteen," which has been named the One Book, One Nebraska statewide reading selection for 2014.

(CNN) -- Midway through this month's Winter Olympic Games in Sochi, Russia, there was a bright and glorious full moon that lit the night sky high above the Earth.

Down below, men and women from around the world competed for medals on behalf of their countries. As usual, special attention was paid to the contests between American and Russian athletes.

On Sunday the closing ceremonies in Sochi will lower the curtain on the Winter Games. The ceremonies, as is tradition, are expected to center on two themes: competition, and the common ground that exists between different nations.

The view of that full moon during the Olympics, though -- so far away from the sights and sounds of the athletic contests -- brought to mind an era, not so very long ago, when competition between the United States and what was then called the Soviet Union was a much more serious game than anything played out on ice rinks or ski slopes.

There were two quotes that galvanized the world back then, two quotes that set the urgent game in motion.

The first was from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. He spoke the words in 1958, directed at Western nations and their capitalistic way of life. Translated from the Russian language, the words appeared in banner headlines in big cities and small towns across the United States:

"We will bury you."

In an America already on edge during the stare-down atmosphere of the Cold War, it is difficult to imagine Khrushchev's warning being any more unequivocal than that.

The second quote was from President John F. Kennedy, delivered in 1962 at Rice University. Even now, the concise confidence of his pledge, the contrast in tone from what Khrushchev had said, is stunning:

"We choose to go to the moon."

Neil Armstrong's famous quote analyzed

Neil Armstrong's famous quote analyzed  See moment lunar rover lands

See moment lunar rover lands  Jade Rabbit begins exploring the Moon

Jade Rabbit begins exploring the Moon Just like that. That impossible thing -- that thing no one had ever done, that thing that all but defied dreams.

And, in case anyone missed the extent of his determination, Kennedy explained why the United States was going to attempt such feats: "not because they are easy, but because they are hard ... because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win."

Talk about high stakes. The United States had been woefully behind the Soviets in the space race. Now the president was promising to go to the moon, not just someday, but "in this decade."

It still seems almost beyond belief, except that it happened.

The race into space that followed those two famous declarations -- "We will bury you" and "We choose to go to the moon" -- mesmerized the nation in ways difficult to describe for those who were not born in those years.

There was one day in particular, early in the effort, when the United States was still trying to catch up with the Soviets and put a man into Earth's orbit. It was in 1962 at Cape Canaveral, Florida. Walter Cronkite, reporting for the CBS television network, was doing his best to be dispassionate and objective as the giant Atlas rocket, with an American inside the tiny capsule atop it, thundered fearsomely into the skies.

"Flight seems to be on target so far," Cronkite said. "Looks like a good flight."

And then the emotion of it all, the importance of the contest at hand, overtook him. If it is possible for a baritone voice to keen, that's what it sounded like: so unexpected and so right, a proud and almost prayerful keening as the rocket lifted:

"Oh, go, baby!"

Then, not long after, a disembodied voice from beyond where anyone could see, the voice of the man alone in the capsule, John Glenn, telling a waiting world that he was in orbit and had achieved weightlessness, that he was free of the Earth's gravity.

The sound of that faraway voice on that day, the flat Midwestern cadence, no more tense or jittery than if he were back in his hometown of New Concord, Ohio, ordering a cheeseburger and a milkshake at the corner hangout:

"Zero G, and I feel fine."

The United States would win the contest; Kennedy was dead before the end of that decade, but, just as he had vowed, Americans walked on the moon by the time the 1970s commenced.

There have been only 12 people in the history of humankind who have stepped onto the moon. All were Americans. The Soviets never made it.

Was it worth the effort? Have the fruits of the victory meant much, in the long run? Those are questions for each American to decide for himself or herself.

This month athletes from the United States and Russia have engaged in spirited and friendly competition at the Sochi Games. No one was threatening to bury the losers of the contests. It is Khrushchev himself who is now buried; he has been gone since 1971. Today, in space, Russian cosmonauts and American astronauts circle the Earth in harmony together, traveling aboard the International Space Station.

A different world in which we all live. The old race -- the race to conquer space, that deadly earnest competition -- is consigned to history. On Sunday, two weeks of beautiful and immeasurably less momentous games will come to a close at a stadium in Russia.

And above those games this month, there was that moon. A reminder of a time when, in ways sometimes difficult to recall, anything at all seemed somehow possible.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Bob Greene.

NASA says an object about the size of a small boulder hit the Moon in Mare Imbrium on March 17, creating an explosion bright enough to be seen on Earth. "It exploded in a flash nearly 10 times as bright as anything we've ever seen before," says Bill Cooke of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office.

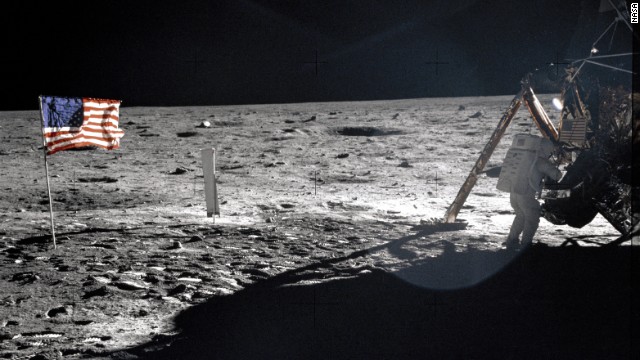

NASA says an object about the size of a small boulder hit the Moon in Mare Imbrium on March 17, creating an explosion bright enough to be seen on Earth. "It exploded in a flash nearly 10 times as bright as anything we've ever seen before," says Bill Cooke of NASA's Meteoroid Environment Office.  Astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969.

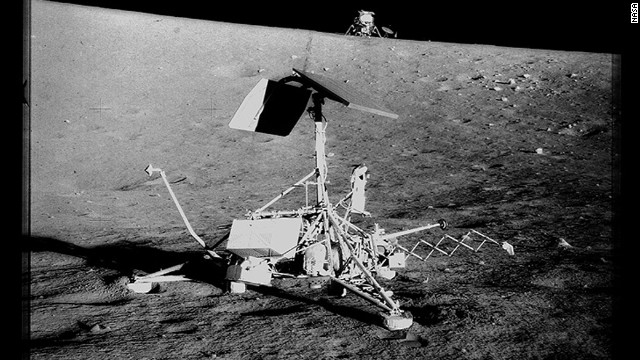

Astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first man to set foot on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission on July 20, 1969.  Surveyor 3 spacecraft landed on April 20, 1967, to support the coming crew of Apollo 12. The objective of the Surveyor 3 was to provide data for research on "soft landings."

Surveyor 3 spacecraft landed on April 20, 1967, to support the coming crew of Apollo 12. The objective of the Surveyor 3 was to provide data for research on "soft landings."  This image is part of 27 separate frames taken by Charles Duke that shows the Apollo 16 landing site in the lunar highlands on April 23, 1972.

This image is part of 27 separate frames taken by Charles Duke that shows the Apollo 16 landing site in the lunar highlands on April 23, 1972.  Apollo 17 mission commander Eugene A. Cernan makes a short checkout of the Lunar Roving Vehicle during the early part of the first Apollo 17 extravehicular activity at the Taurus-Littrow landing site.

Apollo 17 mission commander Eugene A. Cernan makes a short checkout of the Lunar Roving Vehicle during the early part of the first Apollo 17 extravehicular activity at the Taurus-Littrow landing site.  The Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, found the presence of water molecules when it was purposefully crashed into the moon to collect data from beneath the surface on October 9, 2009. The satellite is shown in this artist's rendering.

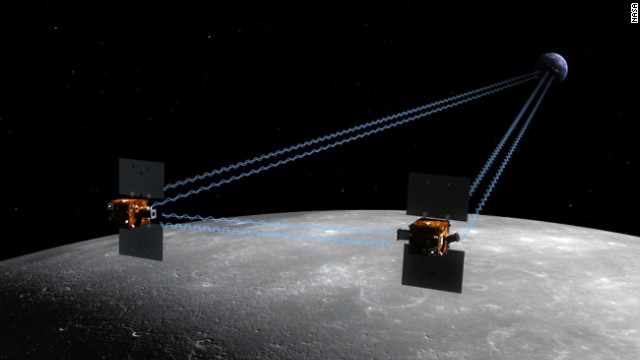

The Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, found the presence of water molecules when it was purposefully crashed into the moon to collect data from beneath the surface on October 9, 2009. The satellite is shown in this artist's rendering.  The Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory, or GRAIL, was launched in 2012 to detail the moon's gravitational pull using two separate space crafts, named Ebb and Flow.

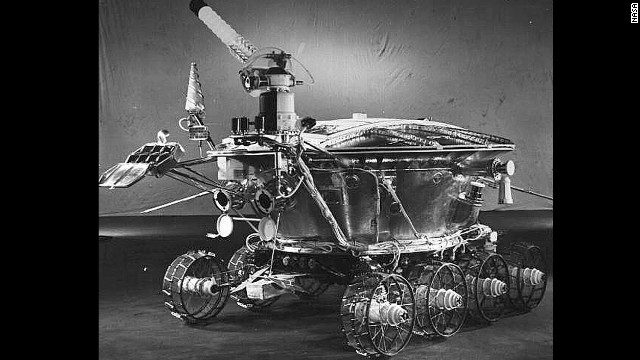

The Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory, or GRAIL, was launched in 2012 to detail the moon's gravitational pull using two separate space crafts, named Ebb and Flow.  The Soviets' Lunokhod 1, the first unmanned rover, landed on the moon on November 17, 1970.

The Soviets' Lunokhod 1, the first unmanned rover, landed on the moon on November 17, 1970.

No comments:

Post a Comment